Some well-meaning person tries to help us make a choice by appealing to the power of emotion and feelings. Make no mistake about it, though; a conscience is a powerful and good thing. A conscience properly trained is an effective guide, but one improperly trained will occasionally or often lead to the wrong decision.

Consider the case of the apostle Paul, whose conscience misled him, though he obeyed it without question. After persecuting the Way of faith for many years, his conscience was confronted with its error and was cleansed and made practical again.

How can we build a conscience into a positive force in times of decision? The answer is simple. Your conscience can only be an effective guide when God is its teacher.

Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary defines conscience as "the sense or consciousness of the moral goodness or blameworthiness of one's own conduct, intentions, or character together with a feeling of obligation to do right or be good.... conformity to the dictates of conscience."

In the New Testament, conscience is translated from the Greek word, suneidesei, similarly defined in Thayer's Lexicon. To put it perhaps more simply, conscience is an innate feeling of right and wrong and an equally innate but powerful sense that right should be executed. Therein lies the benefit and limitation of the human conscience, for feelings are not always trustworthy and not everyone has such a positive conscience. Conscience is not an innate knowledge of what is actually right and wrong, but a sense or response to right and wrong.

Consciences are random and subjective, often shaped more by

environment and worldly considerations than honestly moral ones. It

is likely that no two consciences are perfectly alike; the standard

changes from person to person and from occasion to occasion, making

an untrained conscience untrustworthy.

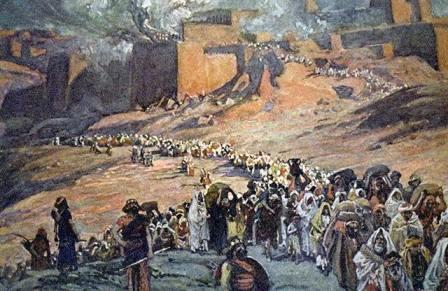

The apostle Paul had been dragged before the Jewish council to

answer charges of blasphemy and other crimes against Judaism and

Jehovah, as recorded by Luke in Acts 22. His greatest crime

in their eyes was preaching that Jesus was the Messiah and so he

began his defense by reminding them that he was once the greatest

persecutor of all. "I persecuted this Way to the death, binding and

delivering into prisons both men and women ... and went to Damascus

to bring in chains even those who were there to Jerusalem to be

punished" (Acts 22:4-5).

His attitude toward Jesus was dramatically changed, however, when he met the Lord on the road into that city. Instead of Damascus being just another stop on Paul's persecution tour, it became the city where he obeyed the gospel, through his repentance, confession and immersion in water. Paul left persecuting to join the persecuted (Acts 22:6-16).

His life was now the opposite of what it had been previously and is confronted with the reality that he could not have been right both before and after his conversion. And yet, he tells the council, "I have lived in all good conscience until this day" (Acts 23:1). Although he obeyed the dictates of his conscience without question on both sides of the creek, it was misleading him on the far side.

Within himself, he felt a strong sense of zeal for God but misdirected it and actually committed sin by obeying the dictates of his conscience. Thus is the danger of obeying an untrained conscience that it may make one chief among sinners in his misguided zeal to do good (Romans 10:1-4; 1 Timothy 1:15).

Still, why should we assume that Paul's conscience is trustworthy now rather than before? The high priest had Paul struck on the mouth because he thought the apostle had digressed from a good conscience to an evil one. A good, properly trained conscience is one that is true to God's word and evidences the individual as a disciple of Christ's (Romans 2:15).

When Paul obeyed the command of Ananias to be baptized and wash away his sins, he was effectively cleansing his conscience by obeying the Christ he had formerly persecuted and repenting of the misdeeds of his untrained conscience. According to the Hebrew writer (which may be Paul himself), his evil conscience was cleansed from dead works when his body was washed with that water and figuratively there sprinkled with the blood of Christ (Hebrews 10:22, 9:13-14).

Moreover, we have the testimony of the apostle Peter to inform us that genuine conversion, sealed in water baptism, benefits one's conscience. Peter writes, "And corresponding to that [Noah's voyage], baptism now saves you -- not the removal of dirt from the flesh, but an appeal to God for a good conscience..." (1 Peter 3:21, NASV). The New American Standard Version gives a fitting translation of the phrase, hapax legomenon, which indicates the cleansed conscience is requested in baptism, rather than possessed before and even without immersion in water.

From the point of conversion, however, the conscience must daily be trained to act not according to a subjective, human concept of goodness, but according to God's divine standard of right and wrong. Thus Paul states that he made it his aim to be well pleasing to God (2 Corinthians 5:9). We are told to discern God's will by reading and to train our consciences by living it (1 Peter 3:15-16). The Christian conscience will often oppose the world's, which is influenced not by objective standards, but traditions, situations and self-service.

Some have a form of conscience, but it is not truly instructed out of God's word. It is ultimately ungodly, although it may appear just in the measure of the world. The humanistic conscience is probably the most common form of conscience today, and basically, it possesses some fine qualities. It gets very fuzzy around the edges, however, and actually overturns Bible morality if necessary to maintain anyone's self-esteem. The humanistic conscience makes subjective judgments based on situation ethics (e.g., lying is generally wrong but is sanctioned to save someone's feelings or hide an embarrassing mistake). The humanistic conscience is constantly drifting further from the Bible because every individual is empowered to stretch it as he feels necessary.

Some ungodly consciences are even beyond this. They are seared as with a hot branding iron, past feeling the pangs of a godly conscience at all anymore (Ephesians 4:17-19; c.f. 1 Timothy 4:1-2). These commit sin without regard to conscience or God's law, for they no longer can care (Romans 8:7). They feel no remorse, except for getting caught, and are completely untrustworthy. As branding an animal kills the nerves in that flesh, so a person who violates God's will repeatedly dulls the senses against feeling the power of rebuke in the conscience.

For this cause is the first foray into sin a serious matter and not so easily dismissed as harmless experimentation. For example, one can witness this gradual spiritual decay in those who grow to forsake the assembling over time. They begin by skipping Wednesday class just once for a concert, progress to skipping it altogether, and graduate to trimming parts off of the Lord's Day to pamper themselves. Sunday night becomes their television time. Sunday morning is mattress-hugging time. At first, it felt a little sickening to skip services; now it doesn't hurt at all. Sin, if repeated often enough, becomes its own addiction and anesthesia.

In the process of developing an ungodly conscience, a person often takes a cleansed conscience and gradually defiles it by refusing on occasion to obey its dictates (Titus 1:15). A conscience is defiled by knowing the right thing to do and choosing evil instead (James 4:17); this is the process of branding a conscience with a hot iron until it is beyond feeling and therefore useless. The good conscience is reshaped into something most ungodly over time by justifying sinful behavior as unavoidable or ultimately beneficial to men. Ungodly consciences are made by exploiting weaknesses of faith.

We however covet that conscience which is godly, disciplined by the word of God and able to overcome the wiles of the devil to do the right thing. Such a conscience feels the pangs of guilt when sin is committed or considered and is deeply motivated to do what it discerns is best. This conscience is trustworthy as an "inner voice" which one can hear and generally follow.

A godly conscience demands constant labor to be pure in God's sight and yet it must be carefully guarded from worldly influence lest it also be defiled. "This being so, I myself always strive to have a conscience without offense toward God and men" (Acts 24:16). A godly conscience is threatened by peer pressure, sin-filled entertainment and the prevailing opinion that iniquity in moderation in a preferable compromise between extreme evil and extreme holiness.

Don't trust your conscience unless it reflects objectively the will of God. And even then, constantly examine it to make sure it has not strayed (2 Corinthians 13:5). --- Watchman Magazine